A few posts have been saved in draft form, but never published because of time constraints. There are a few blogs that I follow and really enjoy the daily or weekly updates and have noticed that sometimes even the smallest posting about historical endeavors, thoughts or projects really inspires me.

With that notion in mind, I have come to the realization that trying to post fairly in-depth research and then undertaking the creation or acquisition of the reproduction based on the research is well-meaning, but not an easy commitment with family, career and going back to school. In other words, it makes it to where I can't post anything for over a year and I don't like it!

Let's face it: It is just a hobby and past time! It is still an obsession on my part, but most of my time resources have been and continue to be used elsewhere. (Much to the delight of my wife!) Remind me, we need to have a conversation about how everyone's spouse fits into living history. Mine considers my history obsession a "mistress".

Before I get to the history part, we welcomed another addition to our home. On February 4, Ella Marie was born and at the moment she is sleeping peacefully in the bouncy seat. Always with a historical mind, it pleases me that both of my children can easily have 18th Century French names: Jacques and Marie! I have also adopted the French name of Philippe Robert, habitant du Kaskaskia for myself, since it is my given first and middle name. With another stroke of luck, Robert happens to be a very common French name. Things keep falling into place! I hope to receive a dit name. I will take suggestions into consideration...

Now for what I have been working on, researching, spending too much time on, etc:

First, I have been looking at several Papal artifacts and recreating rosaries for 18th century reenactors. Catholicism was a major part of French society at the time and my thoughts lead me to believe French reenactors should have a fair amount of Catholic accoutrements in their kit.

This led me to other small projects, including obtaining an original Jesuit cross to use for the molding of "lead" crucifixes found at the Guebert Site at Kaskaskia. My reproduction is a lead-free pewter, although I have no personal objections with keeping a lead one.

As a shameless plug, some of my work is pictured and available on the "Philippe Robert, habitant du Kaskaskia" Facebook page. Please like the page if you visit it. I certainly appreciate it!

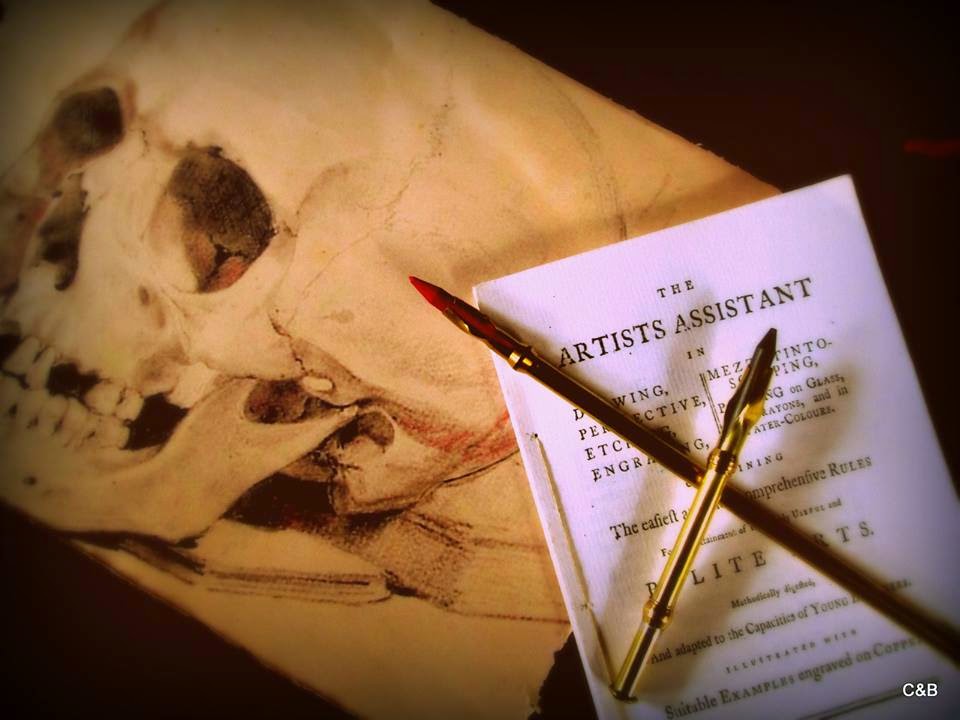

I also am proud to offer my porte crayons for the writer and artist.

Other items in the "research and development" stages are the creation of hawk bells, awls, fire steels, petit calumets, lead bale seals, Jesuit rings and just about anything else that would be common artifacts found in a Nouvelle France context. If you have suggestions or an interest in something that you would like to see on the trade blanket, please contact me.

Now then, on to something new:

An Introduction to Research Methods

It is my recommendation that anyone interested in living history to join Facebook (if you have not already) and begin looking for groups with similar interests. You will find groups devoted to anything from using stuff that looks old, but is not copied from original historic items to groups that are die-hards down to the construction of their clothing.

My broken record mantra is "it is a personal journey", so join these groups with the caution that some folks are satisfied with primitive camping and "bushcraft" types of stuff, while others will not compromise their goals by making historically-researched items without using historically-researched tools. I respect both, but believe it is important for people to understand the focus of a group and play by the rules of the sandbox in which they are sitting. It is easier to make friends that way and friends will help you!

Another personal lesson I have learned over the years on message boards and internet groups is to ask questions, but offer up what research you already have done. This shows people you are serious about your intent and that you are not an information moocher. The research offered should be more than just a Google search, but make sure you have at least done a Google search. People do expect you to research your own stuff eventually. I am so thankful for a handful of friends that have helped me to not be scared of primary documents! (Thanks, Chris Wills.) Now we all share information freely, which advances our historical perspective exponentially!

You may have people at all research levels offer advice. They really do mean well. It may be anywhere from an opinion to images or quotes from primary sources. If there isn't a primary source behind it, don't trust it. Use the primary source to further verify the conclusions of the person offering the advice. My best friends in the hobby will precursor any "conjectural" statements before they offer educated advice. Those are the best kind of friends.

Some people on the internet are brash, crabby and/or hardheaded. Remember that even a crank may offer tidbits of wisdom. Don't dismiss the advice. Gems are sometimes found in the mud.

Above all, if someone is giving primary documentation, don't try to disprove them with secondary documents or a website that has no historical context or contains only opinion. This will shut down further help pretty quickly. Life gives us all situations where we need to smile, nod and move on. No one likes to be asked for help and then have the help they offer be dismissed with an argument.

Right now, it is important to understand the difference between "primary" and "secondary" research sources before searching:

Now then, where to start with research? I will share what works for me.

Here lately, I have been on a "Jesuit ring" kick and wanted to know more about them in hopes of maybe making some. Here is a little "flow chart" that flows through my head when I first get started:

My Jesuit ring search led to several images. I first focus on "credible" resources like this picture found from the National Park Service:

Clicking on the picture in the Google image search yields a trip to the NPS' Grand Portage website, with more information about the pictured ring. Connected to the site is even more information about personal adornment items found at the historic site:

Being the cheap-skate that I am, a search for the cheapest copy of this book had begun and fortunately the Mackinac Park people (I am guessing the gift shop?) had the most economical copy. There were also several other titles that interested me and have great information on the material culture of the site. Right now, it is important to understand the difference between "primary" and "secondary" research sources before searching:

Now then, where to start with research? I will share what works for me.

Here lately, I have been on a "Jesuit ring" kick and wanted to know more about them in hopes of maybe making some. Here is a little "flow chart" that flows through my head when I first get started:

Clicking on the picture in the Google image search yields a trip to the NPS' Grand Portage website, with more information about the pictured ring. Connected to the site is even more information about personal adornment items found at the historic site:

Very quickly, with just the few strokes of a keyboard a person can unlock the answers to a historical question and find even more information on a related topic, which allows the research to continually branch into other topics. If something is interesting, I screen shot, save the page as a web archive or find some other way to make note of it on my portable hard drive. My virtual file cabinet is constantly being added to as more information on a topic is found. Just like a physical file cabinet, I have information filed by topic and sometimes I try to cross-reference related topics (i.e. a painting shows both ceramics and kettles, it gets stored in both topic files).

Above is the quick and dirty search to get a person going on a topic. Just one source is not nearly enough evidence to support an item's prevalence, especially if a person is wanting to prove an item as being commonplace, which is a big part of my initial goal in the hobby. This is where archaeological reports (usually in hard-copy print) come in handy.

For my Jesuit ring example, I started looking at other French-occupied sites in the Midwest: Grand Portage, Michilimackinac, Fort de Chartres and Kaskaskia to name a few. The search for an archeological report quickly led to this book:

When the Jesuit ring book arrived, it is chock-full of examples, tables that classify common shapes and just about anything else a person on a Jesuit ring kick would want to know about the specific artifact. With just that small amount of researching, I can conclusively make these general statements:

- Jesuit rings of the 1600's generally had raised, cast artwork and iconography. Examples from the 1700's are typically engraved or stamped in a crude manner. It is believed a goal in production was to produce the rings quickly and more economically during the latter time period, possibly being engraved on the American continent with simple tools.

- The octagonal plaque (face) on the ring is the most prevalent shape, followed by heart shaped plaques.

- Rings were often very small, typically sized to fit the fingers of a small woman or child.

For a minimal amount of work and investment, I was able to glean a basic understanding and set of answers to my historical question. Best of all, I have an initial set of research sources that can be revisited as time and interest allows.

Research does not have to be daunting or time consuming. It is whatever you wish to make of it. However, it is worthwhile to be able to make informed decisions when choosing gear and have the ability to provide sound evidence for your choices.

Happy researching, everyone!